Research Note | 13 Jun 2024

Cost escalation pressures are easing but key risks remain

Construction & Infrastructure Consulting Team

Summary

Construction cost escalation has slowed from the unprecedented inflationary spike experienced by the sector in 2022 and 2023. The recent surge in construction costs was primarily driven by supply-side factors; commodity market volatility and the energy cost crisis has shifted up manufacturing and transport costs, compounded by supply-chain disruptions from the lingering impacts of the pandemic. International drivers of construction cost growth are now moderating but inflationary pressures remain – the drivers have just shifted towards domestic factors. Without substantial improvements in construction industry productivity, this presents risks for a significant reacceleration in construction cost escalation later this decade.

CPI Inflation versus Construction Cost Escalation

It may come a surprise to some outside of the construction industry, but construction cost inflation (typically referred to as cost escalation), has historically outpaced growth in broader household-based inflation measures such as the Consumer Price Index (CPI).

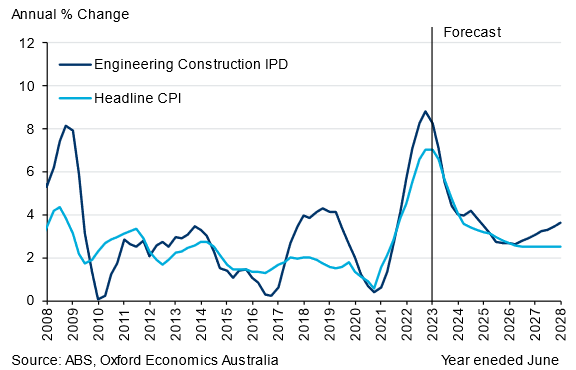

Fig. 1. Engineering Construction IPD and Headline CPI, 2008-2028

Since the mid-1980s, when the ABS first published its Engineering Construction Survey, growth in the Engineering Construction Implicit Price Deflator (a broad measure of price growth in engineering construction work done) has averaged 3.4% growth per annum against 3.1% per annum average growth in the CPI. Since the 2000s, this difference has only become starker, with the engineering construction IPD growing at an average rate of 3.7% per annum against 2.8% per annum growth in the CPI.

Importantly, this difference is not due to well-known and regularly observed “çost blowouts” on major construction projects (which, by the way, are mainly the result of poor front end project cost estimation and/or the crystallisation of risk which should have been included in contingency). Rather, it is because construction cost indices and the CPI are measuring fundamentally different things. The CPI is focused on a representative basket of goods and services purchased by households, while output-based construction cost indices such as the engineering construction IPD reflect movements in prices for construction inputs, including project owner (client) costs as well as margins of construction contractors.

Movements in prices for raw commodities such as oil, coal, copper and quarry products, upstream manufactured products such as steel, cement and concrete, as well as construction industry wages, tend to have a proportionately greater impact on construction cost escalation than the CPI as they occupy a greater share of the construction industry expenditure than in the representative ‘basket’ of goods and services purchased by households. And prices for these items have generally increased at a faster rate than the CPI given supply/demand imbalances in global and national markets over the past two decades. Furthermore, monetary authorities such as the RBA specifically target CPI to remain within a 2-3% growth band – and are prepared to take corrective action when price growth moves outside the band. There is no specific target set to ”correct” unusually high growth in construction costs.

The recent cost escalation surge

The recent surge in economy-wide inflationary pressures has highlighted the increased exposure of construction cost escalation to domestic and international market factors, with a range of relevant price indices indicating growth in construction costs exceeding general inflation as measured by the CPI. Construction cost escalation grew at record rates over financial year 2022 (5.7%) and 2023 (8.2%) – again exceeding growth in the CPI – underpinned by the combination of various severe shocks to demand and supply in domestic and overseas economies.

Essentially, deflationary pressures during the onset of the pandemic in 2020 (including a collapse in oil prices) gave way to a sharp rebound in global economic activity in subsequent years– supported by fiscal stimulus (partly targeted towards public infrastructure investment) and the loosening of movement restrictions. The strong recovery in demand challenged market capacity, and this was exacerbated by the supply shock related to sanctions on Russian exports following the invasion of Ukraine in February 2022. These factors culminated in the global energy crisis, wherein natural gas and steaming coal prices reached record highs, including benchmark oil prices returning to 2008 levels. The surge in energy commodities shifted up transport and electricity costs, which was further fuelled by flooding along the east coast of Australia which disrupted coal supply.

Other factors also took their toll: the outbreak of a global shipping crisis compounded disruptions in industrial production, with rising demand for containerised goods and a lack of shipping capacity driving up transportation costs. Import prices were further hoisted by the depreciating Australian dollar, which cycled downwards throughout 2022 and 2023.

Construction price growth now moderating… but not reversing…

As shown in Figure 1, FY2023 represented the peak in construction cost escalation growth (with the quarterly peak in growth being the December 2022 quarter of that year). Since then, there have been significant price falls in key energy and metal commodities. With much of the data for FY24 already in, nominal benchmark Brent oil prices ($A/barrel) are expected to average a small drop through FY24 compared to the average price in FY23, steaming coal prices should more or less halve and LNG prices should end up around 25-30% lower than the average for FY23. Prices for steel products, such as beams and sections (captured in the ABS Producer Price Index) have already fallen 13% in the year to March 2024.

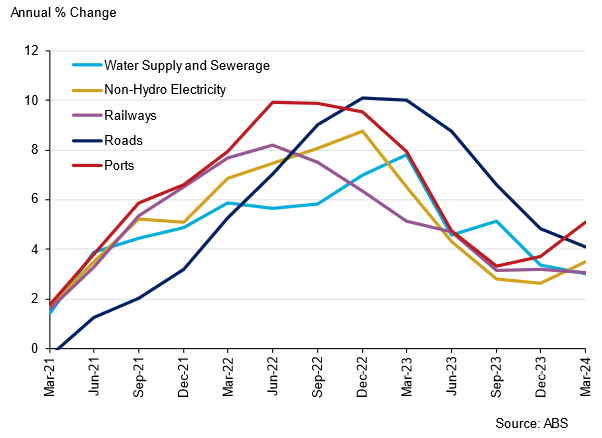

However, while there has been a significant fall in some key construction input prices, overall measures of construction cost escalation have merely seen their growth slow rather than reverse outright – as characterised by sectoral engineering construction implicit price deflators sourced from the ABS in Figure 2 below. Worse, latest data (March quarter 2024) suggests cost escalation may be ‘bottoming out’ at a rate above 2% and is starting to reaccelerate.

Fig. 2. Annual Growth in Sectoral Engineering Construction IPDs

… while risks are emerging for a reacceleration in construction cost escalation

So why haven’t construction prices fallen? Essentially, price declines for some key construction inputs is being offset by accelerating prices for other inputs. Instead of international factors driving escalation, domestic price pressures are now driving escalation based on the strong pipeline of construction activity. In particular strong demand for construction labour and local construction materials is driving stronger growth in construction wage outcomes and prices for inputs such as quarry materials, cement and concrete. ABS Wage Price Index data shows that wage growth in the construction sector has accelerated from a low of 1.5% in 2020 to 4% currently (and higher again in some states such as Queensland), while prices for quarry products have risen more than 20% over the same period.

At Oxford Economics Australia, we see significant risks of cost escalation once more surprising on the upside in coming years – even if the RBA is successful at quarantining CPI growth within its 2-3% target band. From as early as FY2026 we are forecasting another ‘decoupling’ of construction cost escalation and the CPI, with measures such as the engineering construction IPD potentially growing at more than 4% per annum by FY2028 and pushing even higher towards the turn of the decade. Escalation of this magnitude could easily add $200 million in costs on a multi-year $1 billion megaproject. In our view, key drivers of cost reacceleration include:

- Firstly, the full impact of the latest inflationary episode on construction industry wages which is yet to play out. More Enterprise Bargaining Agreements (EBAs) are to be restruck over the coming 12-18 months which will aim to claw back sharp falls in real wages during 2022 and 2023. This will incrementally ‘lock in’ relatively higher wage growth outcomes for several years.

- Secondly, strong targets for building new housing, energy, water, transport, health and education assets – alongside new investments across Defence, the resources sector and even the Brisbane Olympics – are anticipated to drive a substantial upswing in construction activity later this decade (as discussed in our previous blog) and this will likely sustain demand side price pressure on local construction wages and materials.

- Thirdly, laudable moves to reduce carbon emissions in the construction sector as part of broader movements towards net zero may involve, in the short term at least, a trade off with costs as newer, more sustainable ‘low-carbon’ products and processes (e.g. materials recycling) are adopted. (More research is required here!)

- Finally, while significantly improved over the past year, global supply chains are likely to remain relatively ‘thin’ compared to pre-Covid times and prone to further disruptions/cost pressures from rising demand (as the global economy reaccelerates later this decade) or if future shocks emerge such as geopolitical events (e.g. a ‘Middle East escalation’ scenario), increasing trade protections or even another pandemic. Recent history has shown that global events can have sharp and painful impacts on local cost escalation.

Boosting productivity remains the key

Finally, this outlook assumes some success in reversing the construction industry’s poor productivity performance (and note to the Australian Constructors Association: the cost of poor productivity now well exceeds $56 billion per annum based on the latest data). This is critical not just to minimising escalation risks, but in actually delivering on the many infrastructure and housing promises targeted by the governments across Australia given limited market capacity.

Essentially, the best way of avoiding a high-cost future without sacrificing policy objectives is to reduce our pull on resources through doing things smarter, better and generally making less mistakes in planning and delivery that requires rework. For government and industry this requires more efficient risk allocation and procurement, better front end planning and coordination of the infrastructure pipeline, a heightened focus on education, training and skills retention in the construction industry and a ‘step change’ in the way government and industry implement known technologies (e.g. what’s referred to in the industry as Modern Methods of Construction such as modularisation, prefabrication etc) to boost productivity.

Your Authors

Adrian Hart

Director, Construction and Infrastructure, Oxford Economics

+61 (0) 2 8458 4233

Adrian Hart

Director, Construction and Infrastructure, Oxford Economics

Sydney, Australia

Adrian has over 25 years of economic analysis and consulting experience with Oxford Economics Australia, focusing on the infrastructure, building, maintenance and mining industries. Adrian has undertaken a wide range of consultancy projects for the public and private sector based on his detailed understanding of construction, mining and maintenance markets, their drivers and outlooks, the range of organisations operating in this space and the issues they face. This work includes deeper industry liaison, contractor and competitive analysis, pipeline analysis, demand and cost escalation forecasting, and industry capacity and capability projects for the public and private sector. He is the lead author of major reports but also undertakes briefings and workshops for senior management, board members and industry associations, leads in-depth stakeholder consultation, and facilitates and chairs roundtables between government and industry.

Thomas Westrup

Senior Economist

+61 (0) 2 8458 4208

Thomas Westrup

Senior Economist

Sydney, Australia

Thomas is a Senior Economist with the Construction and Infrastructure team at Oxford Economics Australia. After joining the company in 2019, he has managed or heavily contributed to a wide range of private consulting and advisory work across Oxford Economics Australia clients, with a heavy focus on market capacity, industry analysis, cost escalation, economic impact and workforce capability.

More Research

Post

Australian Non-residential building major project outlook for 2024

A pipeline of major projects (contract value at or above $50 million) totalling $15.4 billion nationally is expected to break ground in calendar year 2024

Find Out More

Post

Australia’s non-residential building approvals set a weak lead

The approvals lead for non-residential building continues to soften, with March quarter 2024 maintaining the recent downward trend in project approvals. While a normalisation beyond COVID continues to impact for some sectors, broader cyclical demand drags are becoming more obvious.

Find Out More

Post

Australian Federal Budget highlights several themes for building

The 2024/25 Federal Budget delivered little to shift the outlook for building construction, although there was modest movement connected to housing, tertiary education, manufacturing, and defence.

Find Out More

Post

Australian federal budget delivers no surprises

The 2024-25 federal budget affirmed the forecast changes we made in the April 2024 edition of our Engineering Construction in Australia (ECA) service. We continue to expect publicly funded activity to average $54.1bn over the five years to FY28, compared to an average of $42.1bn over the five years to FY23.

Find Out More