Blog | 24 Apr 2024

What needs to go right to achieve 15.9 million tertiary jobs by 2050?

Emily Dabbs

Head of Macroeconomics Consulting, Oxford Economics

The Australian Government’s review of Australia’s it’s higher education system could not have come at a more opportune time. Lacklustre productivity growth, tight labour market conditions and skills shortages are major concerns for Australian businesses right now and are also factors increasing demands on Australia’s tertiary education system. The Australian Universities Accord released its final report earlier this year, and against this backdrop of challenging economic conditions it is no wonder that the reception has been broadly positive.

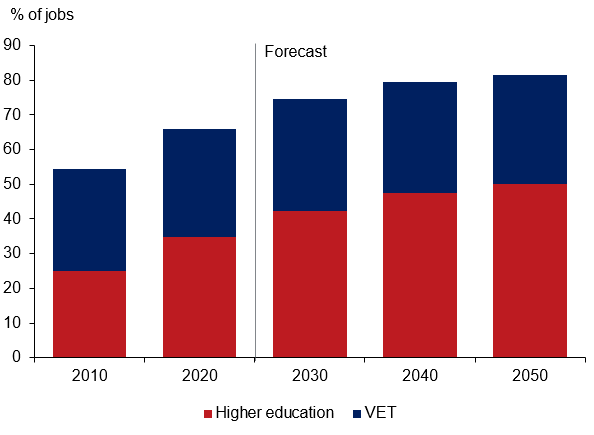

The Accord’s report is just the start of the journey, not the end. Indeed, as part of our report for the Accord we estimated that 82% of jobs will be tertiary educated roles by 2050, with an average 960,000 qualifications needed each year to meet this demand. This is no small feat for the sector to achieve and requires significant growth without compromising on quality.

Fig. 1: Tertiary jobs share of workforce, 2010 to 2050

Source: Oxford Economics Australia – Higher Education Qualification Demand

The Accord’s recommendations provide the foundations for the sector to take on this challenge. However, through our discussions with tertiary education and industry leaders we believe there are three core areas that we need to get right if Australia is to achieve the ambitious targets required to meet the future demands of the labour market.

Funding the sector effectively in a cost constrained environment

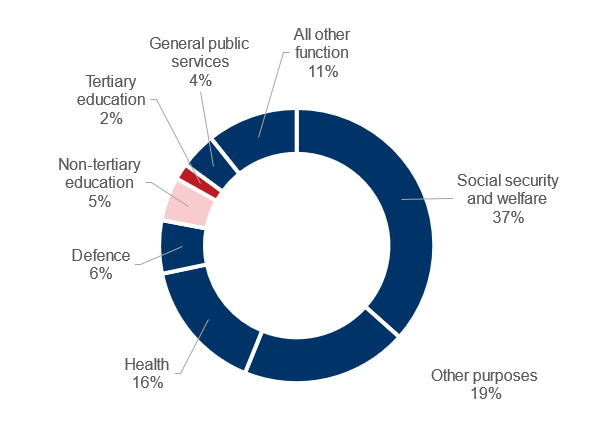

Commonwealth gross debt is estimated to reach 34% of GDP in FY24 and despite recent improvement, structural spending pressures remain. While tertiary education accounts for just 2% of total government expenditures, there is limited room to significantly increasing funds to the sector. The constraint on government funding means we need to ensure that the funds we do have are used effectively to produce high quality educational outcomes.

Fig. 2: Government expenses by function in 2023–24, share of total

Source: 2023-24 Federal Budget

The Accord has identified that the current funding model is not fit for the type of growth that the Australian economy needs. The proposal to implement a needs-based funding system that reflects the cost of delivering education, particularly for equity cohorts and regional based education providers, is a step in the right direction. However, there are no additional incentives for universities to deliver higher quality education above the industry standard. Without any linkage between funding and education quality we risk that universities are incentivised to fill seats instead of providing best in class education.

This is not a new idea, but as previous experience highlights, it is challenging to implement. The Learning and Teaching Performance Fund introduced in 2003 provided additional funding to universities that performed best across a range of metrics such as outcomes and student satisfaction, but without adjustments for the student make- up of these universities it resulted in lower funding for some equity cohorts. The Reward Funding scheme tried to adjust for this but ultimately this resulted in participation and social inclusion being the sole determinants of the additional funding. The more recent Performance Based Funding scheme provided additional funding beyond 2020 levels tied to performance metrics. This scheme faced significant challenges due to COVID-19 which impacted a number of metrics used by the scheme.

Linking funding to quality outcomes ensures that society receives the best return on its investment. It can encourage education providers to invest in new and innovative teaching methods, specialise in areas where they have a comparative advantage, and drive overall improvement across the sector.

Universities also need to look inward to how they deliver high quality education efficiently. The financial viability of Australian universities is under pressure, with just five of the 29 universities who reported their 2022 accounts being in surplus. The return of international students will provide a much needed boost to revenues for the sector, but improving the productivity of universities remains a challenge. Using technology effectively to deliver a high quality education experience to more students is one way that universities can improve their own productivity.

Ensuring settings provide the flexibility needed by our labour market

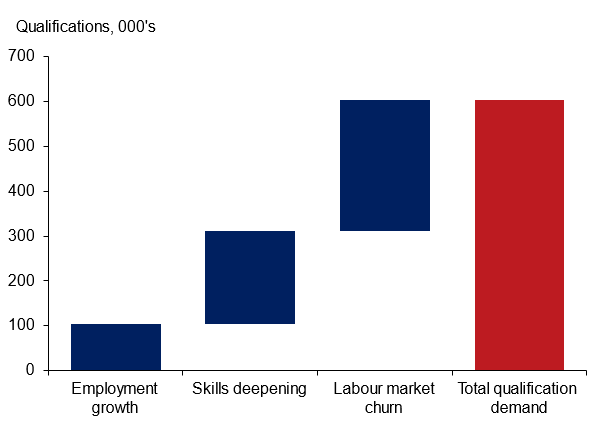

We estimate that around 30% of labour market demand for qualifications will be driven by upskilling and reskilling requirements over the next 30 years as an ageing population and a changing industrial make-up drive life-long learning across the working aged population. Strong cross -sector integration and collaboration between higher education and vocational education will be essential for filling existing and emerging skills gaps in industry, particularly due to the growing nature of skills based hiring practices.

Fig. 3: Change in average annual gross labour market demand for additional qualifications by driver of demand, 2022 to 2052

Source: Oxford Economics Australia – Higher Education Qualification Demand

The Accord has recognised the need for flexibility moving forward, including recommendations for the development of a national skills passport and modular stackable skills. Taking learnings from the sector to date will be critical to ensuring the success of these initiatives.

Cross sector integration is not one -size -fits -all with some fields likely to be more suitable than others. Accounting and early childhood care showcase how cross sector education pathways with strong industry buy-in can be successful. The practical requirements of construction based roles make this a more challenging area to build pathways between VET and higher education. A targeted approach to cross -sector collaboration will be critical to ensuring its success.

Microcredentials are not new in Australia but have recently undergone industry diversification and extending beyond their traditional role of fulfilling regulatory requirements. Growth has been strongest in professional services and IT sectors where industry players such as Google and Microsoft have played a role. The NSW Institute of Applied Technology is an example of how education providers, government and industry can work together to provide accredited and industry recognised training in short-course format. Recognition is vital to the success of microcredentials a, both from a student value and industry legitimacy perspectivend getting industry involved will be critical to achieving this.

One of the largest barriers to more flexibility within the system are the administrative processes required across the various regulatory bodies, particularly when both the VET and higher education sector are involved. The creation of an Australian Tertiary Education Commission to oversee the significant industry transformation is important, but its success will be based on how it can alleviate the barriers within the system and not add further red tape or complexity.

Get in contact with us

Emily Dabbs

Head of Macroeconomics Consulting, Oxford Economics

+61 2 8458 4202

Emily Dabbs

Head of Macroeconomics Consulting, Oxford Economics

Sydney, Australia

Emily leads Oxford Economics Australia’s Macro Consulting team. She has over 10 years of economic analysis and consulting experience, focusing on macroeconomic forecast and analysis. Emily regularly provides strategy support and briefings, and presentations to clients and key stakeholders to support a broader understand of the economic environment and the impact on their business.

You might also like

Post

Global Economic Outlook Conference

It was fantastic to welcome our esteemed clients and guests to our economic forecasting conference in Sydney, Melbourne and online.

Find Out More

Post

2024 Insights: Construction & Infrastructure

Calendar 2024 marks a turning point in the construction and infrastructure industry in Australia, with total construction work done expected to fall in real terms through the year for the first time since 2020.

Find Out More

Post

Op-ed: Is the New Vehicle Efficiency Standards too much of a good thing?

Kristian Kolding from Oxford Economics Australia analyses the New Vehicle Efficiency Standard in the op-ed in The Australian Financial Review,

Find Out More