Blog | 14 Feb 2024

Is the New Vehicle Efficiency Standards too much of a good thing?

Kristian Kolding

Head of Consulting, OE Australia

Proposing to introduce a New Vehicle Efficiency Standard can hardly be a bad thing – particularly when you’re the last developed country except for Russia to do so. Phasing it in over five years to catch up to the US (not exactly known for driving small fuel-efficient cars) doesn’t sound too onerous either. And the weight-adjusted limits is a nice policy nuance that means that you’re not asked to shift your Ford Ranger for a Ford Fiesta – rather it encourages you to shift from a heavy emitting Ranger to a less heavy-emitting Ranger. And if we were to trust the government estimates, then every dollar of cost borne by this policy change will lead to $3 of benefit in fuel costs and the like over time.

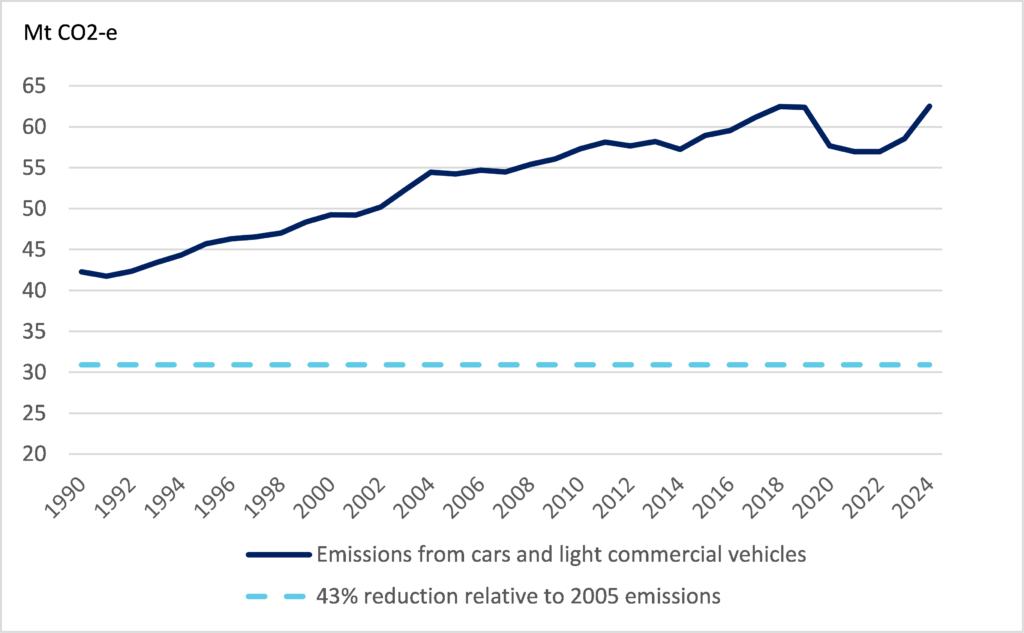

Finally, cutting emissions from the transport sector is essential. Transport emissions make up around 21% of Australia’s total emissions and despite our national commitment to reduce emissions by 43% by 2030 (relative to 2005 levels) – transport emissions are expected to hit record levels this year.

Fig 1: Australian CO2-e emissions from cars and light commercial vehicles

Source: Department of Climate Change, Energy, the Environment and Water Australia’s Emissions Projections 2023, Oxford Economics Note: 43% emission reduction line is an indicative target. Australia has committed to reduce all emissions to 43% of 2005 levels in aggregate. Some source of emissions are expected to reduce further and offset lack of progress from other sources.

That is all good news viewed in isolation. But is it too much of a good thing? Are we risking long-term success by introducing too much change too quickly?

The announcement by David Littleproud – leader of the Federal National Party – that Australia has reached a saturation point for industrial-scale renewable energy capacity is a clear sign that this risk is well and truly alive.\

“We have now got to a saturation point in regional Australia from these renewable energy projects of industrial scale”

Source: David Littleproud, 06/02/2024 reported in Sydney Morning Herald article Call to cancel renewable energy rollout, National declare Bush is Full

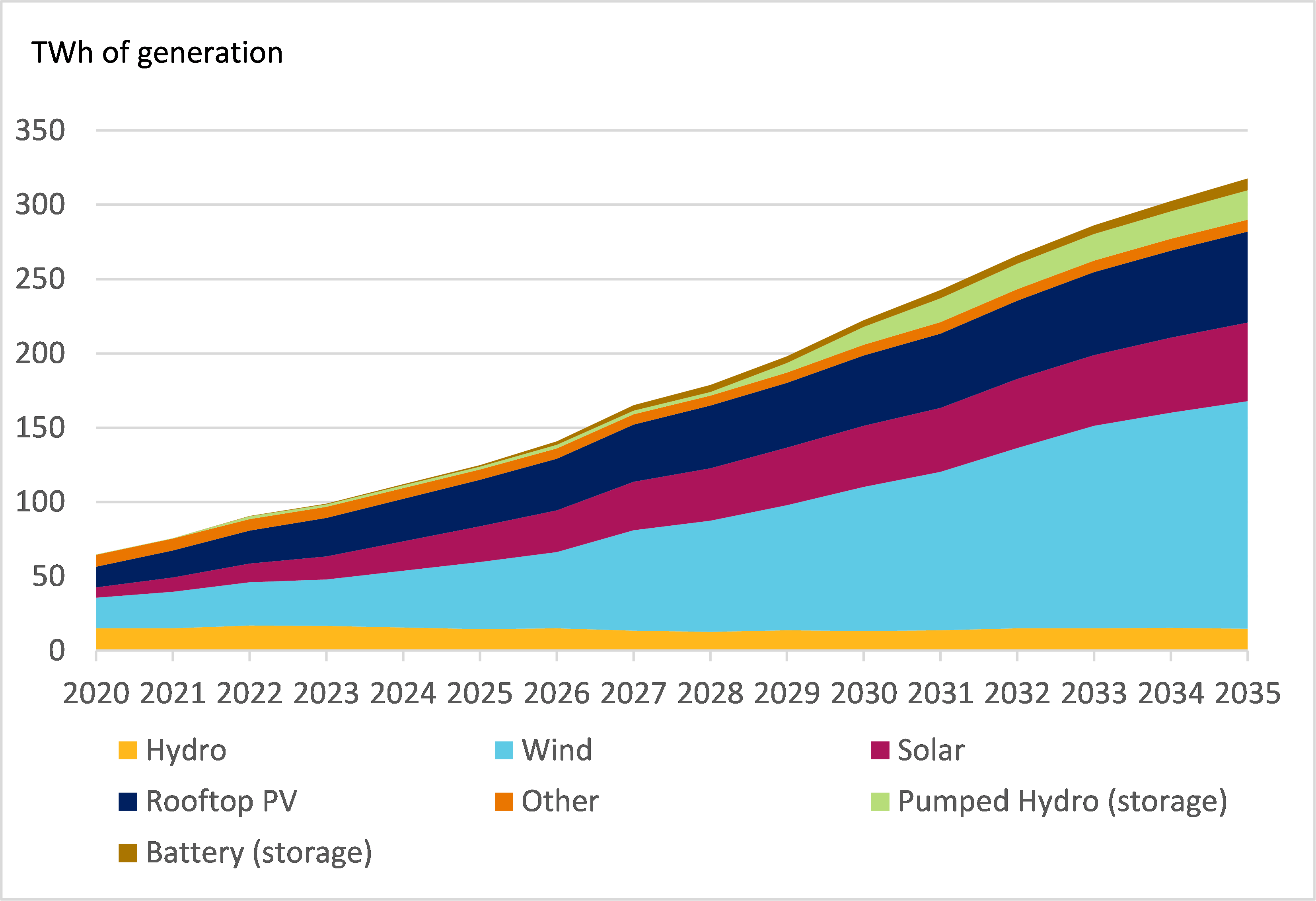

Our analysis suggests that greening the grid must be the first priority if we’re to encourage a smooth transition to a decarbonised economy. Greening the grid will have the biggest direct impact on our emissions by turning off heavy-emitting coal-fired generators. What’s more, access to cheap, reliable, green electricity is also one of the most attractive ways for facilities covered by the Safeguard Mechanism to reduce their emissions. Finally, a shift to electric vehicles will have a significantly greater impact on the environment if the electricity used is green rather than brown.

In a perfect world, we can walk and chew gum at the same time. Or more pertinently, we can introduce the Safeguard Mechanism, the Capacity Investment Scheme, a New Vehicle Efficiency Standard, and more all at the same time. However, we know that it’s not so easy. In particular, our analysis shows that we’re struggling to green the grid quickly enough.

Construction sector capacity constraints, development approvals across various levels of government, and the challenge of gaining a social license to build from regional ute-driving communities is slowing our uptake of renewable energy. Adding fuel to this fire in the form of a ‘ban on utes’ – irrespective of the actual policy intention – is likely to slow things down further in the short term.

Fig 2: Planned renewable energy generation, 2020 to 2035

Source: Oxford Economics, Department of Climate Change, Energy, the Environment and Water Australia’s Emissions Projections 2023, Oxford Economics

Of equal concern is the risk of policy fatigue leading to policy uncertainty in the medium term. we have a history of climate policy uncertainty in Australia and it’s one of the biggest hurdles in the way of supercharging additional private sector climate investment. If the short-term costs of transitioning leads to increased policy change in the medium term then we might find that the gains that we make today will be rapidly undone.

Your Author

Kristian Kolding

Head of Consulting, OE Australia

+61 (4) 1040 9070

Kristian Kolding

Head of Consulting, OE Australia

Sydney, Australia

Kristian leads Oxford Economics Australia’s Consulting team, working with public and private sector leaders to help them prepare for the future by applying relevant economic theory and forecasts to inform effective policy and business strategy development.

Our work

Case Study | Australian Energy Market Operator

Oxford Economics Australia and AEMO’s 2022-23 Energy Outlook Collaboration

Project background The Australian Energy Market Operator (AEMO) engaged Oxford Economics Australia (OEA) to develop economic and demographic scenario forecasts for their 2022-23 energy outlook reports. AEMO, responsible for Australia-wide planning and forecasting publications, required these forecasts as inputs into their modelling processes. The scenarios, outlined in AEMO’s Inputs, Assumptions and Scenarios Report, were developed…

Find Out More

Case Study | Australian Energy Market Operator

Review and validation of AEMO’s cost of capital assumptions for renewable energy investments

Project background The Australian Energy Market Operator (AEMO) engaged Oxford Economics Australia (OEA) to review their cost of capital assumptions for long-term investments in the National Electricity Market (NEM). The review aimed to assess the impact of asset-specific and market risks on the cost of capital. The cost of capital assumptions are key to developing…

Find Out More